In 2019, I welcomed my baby girl into the world and I became a father for the first time. I remember walking into the delivery room draped in protective apparel and being handed this tiny being wrapped in white towels. My heart raced faster than the car I was in en route to the hospital when I had just found that out she was on the way.

“We’ve a method called the Kangaroo Care. You place the baby on your chest, skin-to-skin, and I promise you that bond will last a lifetime. She will love you forever!” the nurse said, with a smile crossing her face.

Now, my daughter is thirty months old and we still share the same bond we did when she took her first sleep on earth in my arms in the delivery room.

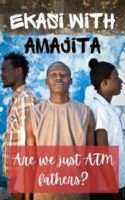

Majita that is precisely what I want us to ringa about today: The importance of being physically present in your child’s life and understanding that being ATM fathers is not ayoba…

Sonke Gender Justice conducted a study and found out that South Africa has an unusually high rate of absent fathers, with nearly half of the country’s children having no daily contact with their fathers.

“Responsible and engaged fathers who share parenting responsibilities benefit children’s development as well as the development of families and communities that better reflect gender equity and respect children’s rights,” the study reads.

But to praat i-vaar, we didn’t need a study to know this! We all know a child whose father only sends Mandelas but never shaya iround to see them. My heart sinks in water to know that amajita are just walking ATMs as they believe ukuthi paying maintenance is sufficient and have little to no contact with their child/ren.

There’s a mutual friend back at home in the Eastern Cape who wanted to visit his child after three months of not seeing her. I found this bizarre as he lived in the same city as her and only works on weekdays. He got on the phone with the mother to find out what gift he could buy for the child as he didn’t know what she liked nor what shoe size she wore.

“Mna I only eWallet the chankura and then her olady does the buying!” he would say gushingly.

Now, he finally hung out with the three-year-old ingcosi, without the mother. Did the child not cry all the way to and during the entire outing! She didn’t know who he was despite speaking to him occasionally on the phone and receiving gifts now and then. And that’s the price he paid for being an ATM father!

Okay, let me not turn a blind eye to some reasons why men cannot be physically there. I know about fathers who work far from home and sending money is the least they could do. I salute you maqhawe! And, that is not all…

In Sonke’s study, participants also mention ilobola-related financial restrictions and ‘damages’. In order to have access to one’s kid born out of wedlock, several African customs require the father to pay fines for offending or disrespecting the female partner’s family. Or for ‘breaking’ the child’s breast. If the father does not pay this amount, he is no longer legally recognised as the child’s father. With high youth unemployment rate in Mzansi, it is no wonder some can’t afford to pay damages.

For those fathers who just ‘choose’ to be ATM fathers, from one tata to another, let us do better majita! Every child deserves to brag to their friends about riding the bicycle and playing dolls with their dad. You can’t reduce your role as a father to ‘moreki’, the one who only buys! Of course, material contribution goes a long way in improving the child’s welfare because we need money to operate in the 21st century at the end of the day. No debate! But can we take it a step further?

Now, before you go to the next braai with amajita, can you take an hour out of your time to bond with the little one? In Maya Angelou’s words, people will forget what you did for them but will never forget how you made them feel!

***

Read the first blog in this series, here

Tell us: Do you agree with the author? Why or Why not?