Voices rising, and eyes – everyone’s eyes – staring at me, seeing me differently, taking my skin off.

Some people look shocked, others scared or worried, but there are some showing a horrible kind of joy.

I can’t look in Fumani’s direction. I’m too afraid of what I’ll see.

“I…” I don’t know what to say, and I have no control over my voice, so that it dips and rises. “I have HIV. HIV and Aids aren’t the same.”

“How did you get it, Ritlatla?” Xongisa calls out.

“Yes, tell us what you did,” someone else joins in.

“Slut.”

“Tell us.”

“Enough now!” Oom Leon is shouting, but I hardly hear him, because the other voices have more power.

Tell us, tell us. It’s battering my ears, waves of sound, voices demanding answers, people judging me.

Shock holds me paralysed and speechless for I don’t know how long. It’s like my mind is trying to close down, block them out, but still I hear them.

I have to stop them, I have to get away from the voices, because Oom Leon roaring at everyone to shut up isn’t working – and yet, shouldn’t I be defending myself?

“It wasn’t anything I did. It wasn’t my fault–” I start, but they drown me out.

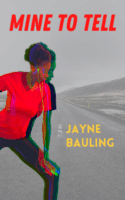

I turn, trying not to see Fumani, and I run.

Laughter behind me now, but also a few voices falling silent.

“Ritlatla.” Someone is calling after me.

Fumani?

“Ritlatla, wait!”

Other voices now, not the cruel ones from before. Maybe Pahlazi’s and Judith’s. What do they want with me? I don’t know. I don’t stop, I can’t.

This running, it’s different from the running I do on the track. This is hard, and it hurts; there’s no freedom in it, and there will be no freedom at the end of it either. I’ll still hear the voices, still see the eyes.

Part of me knows I should stay and face them – and set them right about all the stupid things they believe.

Only, Mahlatse wouldn’t listen to me. Why should they?

“Ritlatla?”

It’s Fumani. Of course he would catch up with me, a sprinter like him. I feel his hand at my elbow, but I jerk my arm free.

“Let me go. Leave me alone.”

I realise I’m crying. When did that happen?

“Ritlatla, stop.” Fumani’s voice is urgent. “I want … I want to understand.”

“Go ask Mahlatse then.” A bitter anger is rising through my tears. “He’s the expert – him and Dzanga. They’ll tell you why you should keep away from me. I shouldn’t have let you … shouldn’t have let you near me, and I’m sorry. I’m sorry.”

I put on a burst of speed, widening the gap between us.

He lets me go, but his voice cuts through the warm, still, Phalaborwa evening air.

“We’re not done yet, Ritlatla.”

Whatever that means.

I run, with my head full of a thousand broken thoughts, and full of nothing at the same time.

I run home, and I cry some more, comforted by Auntie Hlomisa and Gogo. And I think it’s the last time I’ll ever run, and I’m ashamed, because it was a coward’s run, not a brave athlete’s.

Tell us: Was it really cowardice that made Ritlatla run, or was it shock and distress, or something else?