Day 233: Kindness knows no age

After Lephalale, my time in Marken and Baltimore went by without me taking many notes. I had firmly found my Limpopo footing and spent more time with nature than with people. The Limpopo bush had intoxicated me with its mild winter and all the languages that one blade of grass can speak. Until . . .

I lose my smile. It is hot. My bag is heavy and I am grumpy. I am also unfamiliar with the terrain and momentarily estranged from the purpose of my journey. I have another what-on-earth-are-you-doing episode, feel disconnected from the dream and removed from every other living creature. My self-dialogue is negative and full of self-pity. Why is no one else building social bridges? Where are all the others? The beauty of simply being here, with no real care in the world, goes straight over my head.

There aren’t many people around. In the heat of the day the tar road stretches like a shining river ahead of me. I see a speck in the distance, hear a regular squeaking and realise that someone is approaching me on a bicycle. An old bicycle.

When the cyclist gets closer I realise that he is as ancient as his bike. Though I feel thoroughly disgruntled with life on this day, I manage a smile and a courteous greeting. We have many cultures in South Africa, and many customs, but respect for one’s elders, not always practised, is universal. The madala smiles back as he passes.

About one kilometre later I hear whistling and calling behind me. I am too tired to turn around and obstinately continue on my way. Let whoever it is catch up with me, I think uncharitably.

The calling continues, as do I.

And then I hear it again, the unmistakable squeaking of an ancient bicycle. At last I turn . . . to see the old man cycling towards me as fast as he can, holding up a colorful object.

When he pulls up next to me I recognise it. It’s the beanie I saw lying at the side of the road earlier, lost and forgotten. I walked past, thinking fleetingly that it might actually come in quite useful. Now, here it is again. Held out to me in the hands of a stranger. ‘You dropped this!’

How does one give thanks for such a pure act of kindness? This old man has just added almost two kilometres to his trip, and after some questions it becomes clear that he is on his way to church and was late to begin with. He has added two kilometres in the heat of the day for an obstinate stranger.

This experience was very humbling. But once I got over the shame, it lifted my spirits. How could I have taken my eyes off the ball? How could I have felt I was on my own? uBuntu connects us all.

A little later on the same day . . .

‘What’s wrong?’

It is the smallest voice I have ever heard.

Sometimes we forget that our faces are maps that show what corners of our souls we have visited. On this particular day I have had to dig deep just to keep placing one foot in front of the other. She can clearly see this. Children can be like that. They look and see. I can feel her wanting to help me and it is enough to make me want to burst into tears.

I feel incredibly weary today, my whole body is strained.

They sit at the side of the road under a tree, this young girl, some gogos and a few young children. The girl introduces herself. ‘I’m Sandra and I’m fourteen, and this is my granny Dolly.’

They ask me where I am going and are horrified when I mention the next town. They are waiting for a lift to take them there too. ‘No! That’s too far away!’

It is three in the afternoon. I have already walked more than 25km on this deserted road today, what’s another ten or so?

The adults talk among themselves and indicate that they will pay my taxi fare, but after twenty minutes of animated chatter, of which I don’t understand a word, they appear to have a change of heart. Sandra informs me that they have decided, instead, to return to the lodge where they work so that I can stay there with them. They will tell their boss, Chris, who is a very good man, that they want to prepare a room for me at the lodge.

‘Wait,’ I say. ‘Weren’t you going into town?’

Yes, but they can go tomorrow. It is not important.

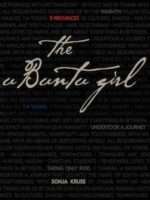

Slowly we walk from the farm gate back to the lodge while Sandra tells me about her family and about the school she attends in Polokwane. They learn about uBuntu in Life Orientation class. She loves English. She loves to write. Her eyes are aflame with inspiration as she stops in the middle of the thick sand. ‘I can help you write your book! I know a lot about uBuntu and my teacher says that I’m a good writer.’

A hot African wind comes to steal her happy words from her mouth. It takes them up and over the tops of the acacias, sending her optimism over the grass and across the scorched plains.

When we reach the lodge, the gogos split up. One goes straight to the kitchen, one rushes off to the linen room and Sandra’s granny sets off to find Chris, who welcomes me and invites me to stay as long as I like.

Something happens to the soul when you fall asleep and follow your dreams into the bush – it allows the mind to meander into a refreshed state. The next morning I awake, stiff but happy. Chris has arranged for Phineas, a tall Venda man who speaks all eleven official languages, to drop me off where I want to go. I am not allowed to leave, however, until the gogos have prepared a de luxe packed lunch so large that I have to tie it to my backpack. Sandra insists on coming along. She does not want me to leave and is dangerously close to tears.

The drive is sombre. Phineas tries to lighten the general mood by telling us that he loves French and is learning Spanish because they have so many Spanish-speaking guests at the lodge. Still, Sandra is shocked when I indicate the long stretch of dirt road leading further into Pedi Trustland where I want to be dropped off. She cries as if she’s losing her oldest friend. I want to relieve her burden, but don’t know how. Then she takes my hand, looks into my eyes and holds up a ten rand note. ‘This is for you, because you will need this.’

When I refuse to accept the money she gets angry. ‘You are not allowed to say no to a gift when someone is giving it to you from all of their heart.’

And then Phineas had another thirty rand for me . . . gifts that made me infinitely sad, because I could not refuse them. By this time we were all crying. There, at the gateway to the Pedi Trustland, we stood, three souls inconsolable at having to part after only meeting the day before. I felt the pain of separation with all of my heart.