Day 73: Braaibroodjies

Maryam told me to ask around for Tannie Brenda if I ended up in Paternoster. Everyone knows Tannie Brenda and Oom Christi and one of the locals selling crayfish escorted me to their home.

Oom Christi has been a fisherman in this community for over 40 years. But Tannie Brenda, oh no: ‘Ek is ’n inkomer. Vanaf die Kaap.’ Even after living here for 33 years, she is still not quite local. They have five children: Brandon; Engel; Jo-Carmin; Vanessa and Logan. They are all very close. The daughters are quite ‘huisvas’, says Tannie Brenda, and hardly ever leave home. Which makes her worry about me and how my parents are coping with this ‘padstappery’ of mine! She tells me that this is a great community. A number of years ago Oom Christi was out fishing, and by 6:00 pm they were still not back on shore. He did not have a compass with him and the weather conditions weren’t great. Luckily they had enough petrol and at 6:30 pm they ended up in St Helena Bay. Everybody was on the beach and helped in whatever way they could.

Tannie Brenda is a great storyteller and her sayings are unique. I overhear her talking about somebody, calling him a bean. She says that he is a bean, because when he is not in the soup, he’s in the shit! She teaches me about the local fishing calendar. Easter is the time for hotnotvis (Kaapse galjoen). In June/July you catch snoek. November to April is crayfish season, and in between they survive on harders (bokkoms, or southern mullet). Every meal in this home is a celebration.

Brandon uses a caravan in the yard as a bit of a ‘kuierplek’ but he gracefully gives it up and it becomes my home for the next two nights. On the third day, I feel like a walk on the beach.

I feel a definite tug from the ocean. It wants me, begs me to go and stick my toes in its now-its-here-now-its-gone waters of changing colour. Single-mindedly I am heeding its call, hardly taking notice of the houses around me, when I hear a voice say, ‘I saw you walking around earlier. You’re travelling light?’

A guy is sitting on a low garden wall with a bemused look on his face. Is he smiling with me or at me? I stop to tell him that the sea is calling me. He grins knowingly, tells me his name and introduces me to his friend who walks out of the house at that moment, braai tongs in hand. I can smell the unmistakable, distinctive South African aroma. It is enticing, even though Tannie Branda’s food has filled my tummy. The men must be curious, because they invite me to lunch. Right there. Right then. The sea will have to wait. I turn my back on it and gladly accept a cold beer. Lunch sounds like a great idea.

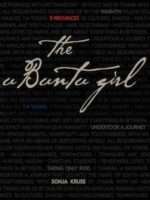

Both men are very curious, so I bare my soul and share my stories with them. Blocking out their real names I nickname them Mr G and Cab. Mr G asks, ’Why uBuntu? What is up with that crap?’

His impression of uBuntu is that it is jargon for something that doesn’t exist. A marketing tool. A political device. Something to authenticate bribery. It is strange to hear others ask questions I have never thought of. Or even those I did think of but chose to ignore. To these two privileged individuals it makes no sense that anyone would do what I am doing just because they have a dream. They question me intensively about my motives and I ask myself – if I had asked myself these things, would I still have embarked on this journey?

My head is spinning with lots to think about. The meat is on the fire and I offer to make something to go with it. Like a salad or some braaibroodjies? Mr G comes back with the news that there are no tomatoes or onions in the kitchen. But obviously his appetite has stirred, because he mentions the local shop. ‘Would you like to go and fetch the ingredients?’

I love walking in Paternoster, but Mr G has other ideas. He hands me the car keys and stuffs a R100 into my hand. I have driven very little in the last two years – not at all for the past few months – and the car turns out to be a big Land Cruiser. I am so daunted by it that the beauty of the situation is totally lost on me: these men don’t know me at all, they have never heard of me or my uBuntu journey and do not care for my ideals or my philosophy, yet I have just been handed the keys to their vehicle.

I try to act nonchalant about driving again. You can do this, Sonja. Key in the ignition. Oh, shit, it’s an automatic. Turn. The engine hums into action. Flick the gear into reverse. Gently I roll back. Clutz that I am, my foot is looking for the clutch and hits the brake instead. I come to a full stop with a mighty whiplash. When I compose myself and check where I am in the bigger scheme of things, I am in the middle of the road. At least I didn’t hit anything. I signal another vehicle to drive around me, rehearse the automatic’s pedals in my mind and eventually manage to drive to the little shop, which ironically is only three blocks away, at a courageous speed of forty kilmetres per hour.

After I have parked I cannot get the damn key out of the ignition. I rack my brain. What am I doing wrong? Shit. Shall I just leave the keys in? I would if it were my car, but this is not my car. Think, Sonja! There has to be a logical explanation and a solution. I solve my dilemma when I put the vehicle into park mode – the key disengages effortlessly.

I grab bread, tomatoes and onions, but when I reach into my pocket for the money, it’s not there. Nor in any of my other pockets. I go back to the car. Look everywhere. Nothing. I replay the last fifteen minutes in my head. Ah, I had the note in my hand when I started the vehicle so it has to be somewhere in the Cruiser. Nothing. It is as though the little purple piece of frigging paper has disappeared into thin air. Become thin air. Great!

In the back of my mind I am aware that the guys may start wondering what has happened to the stranger and their car. ‘OK, guys, so . . . I did not steal your car, but I am back minus the money and without the goodies,’ begins the conversation that is happening inside my head. And I search again, pulling and tugging at things in this very large vehicle.

My backside is poking out of the driver’s door while I search under the seat when Tannie Brenda happens to walk by with her neighbour. She does a double take, ‘But is that not our little Sonja, the one who definitely does not have a car?’ Looking out between by legs I recognise my upside-down host. She sees the thunderclouds on my brow and knows that something is amiss. I explain my predicament and feel tears welling up. ‘Toemaar, my meidjie,’ she says and tells me she’ll replace the money.

How can I accept this when she has already opened her home to me and been so generous? But she waves away my doubts. We bundle into the Cruiser and head over to Tannie Brenda’s. While she fetches the money, I stress about what Cab and Mr G are thinking.

I eventually get back to them with the groceries and they think the story about the whiplash and the lost money is hysterical. They also insist on giving me another R100 to pay back Tannie Brenda (who refuses to take the money).

When we parted Mr G gave me a fancy and expensive Swiss army knife. For my protection, he said. I wanted to ask ‘Protection from what?’ but I refrained. Oh, and those braaibroodjies I made were delicious!