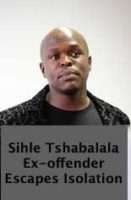

Ex-convicts often experience rejection after prison and consequently find it hard to integrate back into the community, but Sihle Tshabalala (33) was determined not to ‘bar’ himself from a full life as a free man.

“I came out of prison prepared for the outside world. I tried not to take people’s opinions into account, but rather work at myself,” he says.

Sihle hails from one of the notorious townships in Cape Town: Langa. He was raised by a single mother with five brothers. It’s unsurprising he started losing his way just after finishing matric at sixteen years.

“I never had any aspirations to go to varsity to further my studies. We didn’t have career expos or exhibitions at that time. I came out of school with no proper guidance in terms of what was life after matric,” he recalls.

Sihle echoes previous interviewee Suroe Abrahams’

words that townships lack inspiring role models. Because all the inspiring people have left for greener pastures in the suburbs, he says, “Role models in the townships are armed robbers. We grew envying their lives and we were inspired. For me it was also about looking for easy way out and ways to make quick bucks.”

He says the situation at home didn’t make anything easier. “Mom was unemployed and we had to sell pillows just to put food on the table. I started doing business robberies [then went on] to cash-in-transit heists. I relocated to town and I was quite successful for full two years.”

Sihle may have been desperately looking for quick cash but he soon learnt that crime eventually doesn’t pay a cent.

“I got arrested in 2002 and was sent to Pollsmoor prison. I spent the first four years as an awaiting-trialist and was sentenced to eleven years. I then joined the ‘26’ gang and quickly climbed through ranks.”

“I used to smuggle dagga… I made R700 to R800 per parcel. For four years I never ate prison food. I used to smuggle food from outside as well,” he continues.

But he realised eventually that there was only one thing he couldn’t ‘smuggle’ out – and that was his body.

“I knew that if I didn’t get my act together I was going to remain inside for longer than I had anticipated. I started teaching myself how to do Maths and English and gradually grew to become a part of an NPO [non-profit organisation] called Group of Hope, established by inmates in 2002.”

“After my release in 2013, I used the methodology I had developed inside to implement Brother For All, an NPO that deals with high school drop-outs, teenage moms and ex-offenders. We’ve more than 170 students learning programming.”

Sihle says everything he went through was a learning curve for him. “[Nelson Mandela once said] the only thing he missed about prison is time. In prison he had time to think and reflect and so he didn’t come out as an angry man, but a leader. In prison you have to make necessary adjustments and tweakings.”

He proceeds to give his opinion that prisons are no rehabilitation centres. “Prisons breed more criminals for more criminal activities. If you want to make a huge difference then you’ve got to prevent people from having to commit crime. The same principle you use to combat HIV must be applicable to crime as well: prevention is better than cure.”

Sihle says as much as he doesn’t condone crime, government mustn’t turn a blind eye to the causes of crime. “If you really want to change the township people then offer them jobs. If you want to take something away then offer them something in return. That’s what I call the ‘principle of fair exchange’.”

Sihle paid for his mistakes and says everyone should take responsibility for their actions and not point fingers. “Whom do you see when you take a mirror? Do you scratch the mirror when you notice a flaw on your face? Of course not! You scratch yourself and that’s being responsible.”

“A book I read in prison had a note in it that read, ‘If you are looking for a miracle and you can’t find one then be that miracle’. Those words dawned on and sunk in me. Every day I try to be that miracle.”

Brothers For All recently had its first anniversary and Sihle clearly has bigger dreams. He says they’re planning to introduce a digi-truck that will enable them to deliver computer training programmes to people. “The aim is to write a South African version of Steve Jobs, Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg. We currently have sixteen students who’re doing a paid-for internship. We’re rolling out our programs to prisons so we can teach inmates how to code.”

Sihle was jailed for more than eleven years, but his big dreams show that he has emancipated himself from mental prison.

***

Tell us: What did you learn from Sihle’s inspiring story?