Day 123: Magic Portia potion in Orania

Bizarrely, many white people I encountered en route to Orania advised me to avoid it while most coloured and black people thought it would be interesting. Indeed, it was Portia, more than three months ago in Concordia near Knysna, who first encouraged me to come here.

A Zulu truck driver who gives me a lift in the Northern Cape remarks that people have been quite friendly to him when he refuels in the mainly Afrikaner separatist community. So it’s Orania for this orange-haired offshoot of Afrikaner ancestry. I quieten my doubts about the citizens’ possible responses when they learn of my stay in townships. Seizing the moment I get a lift to about 30km from Orania and set off on foot in the mid-afternoon. It is liberating, every time I get out of a vehicle, to be surrounded by nature once again. Exposed. Something happens from my brain outwards – almost as though nature reclaims that part of my humanity that still responds to instinct. A different awareness washes over me and I can see so much more.

I’m busy rewiring my brain when a vehicle approaches from the front. The same vehicle that passed me about five minutes earlier. It pulls over. ‘Do you know how dangerous it is here?’ the man asks almost angrily. ‘Have you not heard about the syndicate kidnapping young women for prostitution?’

They think I’m a foreigner. They introduce themselves as Pierre and Ursula, and when they hear what I’m doing Ursula insists that I come with them. For the next few kilometres I share some of my stories from the past 123 days with the astonished couple. They seem to be really afraid for me. They are happy to drop me off in front of the Afsaal Kafee, but before they leave Ursula and Pierre pray for me and take my cell number. Then I’m alone again. Johan from Kimberley had suggested that I just walk into Afsaal, ask for Karen, tell her that he sent me and that she won’t believe what I’m doing. So that’s exactly what I am going to do.

There are no security checkpoints or booms across the road. I see a garage and a supermarket. I look back in the direction from which I have come . . . just the road. I look forward past the supermarket . . . road stretching on forever. There is a peculiar silence through the daily noise of people and traffic. Something is missing.

When I meet Karen she seems more interested to learn how I know Johan, who works in a computer shop in Kimberley and helped me to download some photos. ‘Sommer net so, Karen.’ She laughs at that and offers me room and board for free.

Her family moved here eight years ago with very little. They were able to buy a house within a year. Karen explains that Orania offers opportunities to many struggling Afrikaners and gives them back their self-respect. ‘Orania is a community that will help you up to a point, then you have to help yourself. And then you can be active in the community.’

Portia would love this.

‘People come here for a variety of reasons. It is commonly misunderstood that all people here are racists. For some, it is a matter of safety.’

She admits that there are racists in Orania. I hear whispers over the next few days. I learn that some locals insist on being called Boers, not Afrikaners, as they believe that Afrikaners include ’traitors’ like FW de Klerk. But either I do not meet these people during my stay or we just never get too political. Still, I see a road sign warning of roadworks ahead – the locals tell me that some kids used white paint to change the colour of the road worker in the sign.

Karen suggests that I report to the town council for a free tour, which includes an overview of the history of Orania and a visit to the Verwoerd Museum. I finally see booms. They seem to be found only at the entrance to residential areas – and they are mostly up. A sign reads: Orania – Afrikanertuiste.

Some houses are made of hay bales, and many use solar power systems. Orania also has its own currency, the Ora. When I notice the date on the back of the note I am about to ask whether it has a sell-by date, then I read the line underneath the handwritten date: USE BY. The local currency promotes local business, which has knock-on effects, environmentally and economically.

The idea of Orania was born in 1966 when Prof Carel Boshoff and Dr Chris Jooste decided that apartheid would never work. They acknowledged the in-justice of depriving the majority of the vote, but also determined that minorities needed extra precautions to protect their culture, language and religion.

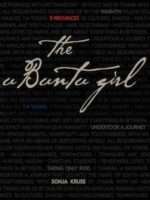

‘Orania is an intentional community where Afrikaner culture can develop and blossom. We people of Orania think of ourselves not as above anybody else, but as one of many in a lovely country. We would love to see a community of communities in South Africa,’ says Lida Strydom when she interviews me for their local publication. The uBuntu Girl is featured in the Orania Nuusbrief.

People smile and wave. They are used to attention around here. During my three nights in town I meet two international journalists and an Australian student of anthropology from Edinburgh University. It seems that Orania is being eyeballed by many countries around the world as a possible model for the preservation of minority cultures. Nelson Mandela and Thabo Mbeki both showed their support.

Before I leave this community, I stand on the stoep and hear that eerie silence again. Now I recognise it. It is the sound of exclusion. This is not my home. I feel that the people of Orania have achieved what they wanted to achieve, but this is not my South Africa. This is another country. My South Africa has kwaito as well as Bok van Blerk. My South Africa has words like ayoba as well as lekker. It has churches, mosques, the whitewashed stones of Shembe worshippers and kerke. My South Africa includes all of those things. My South Africa excludes nothing, and no-one.

I could never live in Orania, but my mind and heart have been opened to the people who call this their home. Thank you, Portia. You were right and I was wrong.