Most gang members are young people – and there’s a reason for this. For adolescents, gangs can be what is known as a rite of passage – a bridge between being a child and an adult. Such rites have been practiced throughout human history, and were guided by tribal elders or shamans. The problem is that with modern city gangs, the urge and the desire for ritual is there – but the elders and shamans are absent. This is when things can go badly wrong.

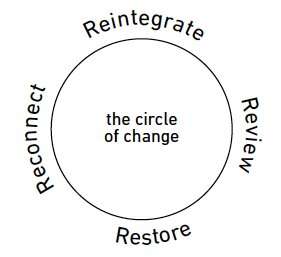

Understanding this, an organisation called Usiko worked out how to take young gang members through guided rituals called the Circle of Change. This is also being practiced at the Chrysalis Academy in Cape Town. It’s a way to provide adolescents what they yearn for and to be able to show their bravery and their cool without the damaging consequences of gang life.

Risk-taking by young people should be seen as a yearning for challenge, guidance and initiation on their road to becoming an adult. In creating a rite of passage ritual there are three stages. You will see that these stages are very much like joining a gang, but do not have the same outcome. These are rituals that modern society has lost, and this absence feeds gang membership. Here are the stages of the Usiko rite of passage programme called Circle of Change

Separation

This is a ‘cleansing’ phase. Young people withdraw from the physical situation that they’re in – their home and environment. They also withdraw from their psychological situation. They prepare to move into another, new phase. They leave behind old practices and routines, parents and their normal friendship group. This phase prepares them for in-depth work on themselves. These are some of the questions young people are asked to consider in this stage:

•Who am I? Am I happy with my life? How have I got to this point in my life? Where am I heading with my life?

Through activities the young person is urged to:

• Take stock of their life;

• Assess their life – the good and the bad, strengths and weaknesses and address the question: ‘Who am I?’;

• Understand the context of their life (what has brought me to where I am?). Look at the situation in which they live (family, community, financial circumstances);

• Acknowledge responsibility for their behaviour;

• Explore the impact of their actions on:

–– Themselves

–– Their family

–– Their friends

–– The victim of the offence.

Transition

During transition, the normal barriers of thought, self-understanding and behaviour are relaxed, opening the way for something new. This is a time of confusion and danger because of the ‘letting go’ of former patterns and the discovery of new personal and social responsibility. It’s a time of uncertainty, excitement and possibilities that leads to something deep and rich.

Transition is a process of breaking down to make a new whole. It is called a ‘liminal state’ because, to a certain extent, the young person’s identity dissolves and life becomes a bit ambiguous and indeterminate. They are neither here nor there, but in between. In liminal space young people need to be encouraged to have spontaneous feelings instead of controlled feelings; spontaneous explanations instead of controlled answers. Young people must be given careful guidance during this uneasy phase.

Wilderness is a perfect setting for transition and is often used in such programmes. It’s an ‘unknown’ place where the unexpected becomes understood as normal. Although wilderness belongs to nature, beyond the city, it’s also a place inside each person. It’s scary, but magical; strange, but exciting.

These are some of the questions young people are asked to consider in this stage. If the young person has been involved in violence or crime, they are asked to consider: ‘What have I done and how can I make it right?’ Specific activities here should guide the young person to:

• Acknowledge the offence;

• Own the offence and the harm or damage done;

• Make up for damage (even if symbolic);

• Engage with restoring self-worth, identity;

• Consider what skills they need to be able to restore the harm done;

• Engage with guilt feelings and a sense of powerlessness.

• Reconnection with themselves (limitations, weaknesses, strengths, unique resources, forgiving themselves);

• Reconnection with their family;

• Reconnection with society or community;

• Reconnection with the offence and victim (symbolic or actual);

• Letting go of the past, releasing;

• Moving from dependence to independence, from reaction to action;

• Establishing independence (What do I bring? How can I change?);

• Accepting who they are.

Reintegration

When the young people have completed the separation and transition stages, they re-enter society with a new relationship to themselves, their society and the earth. This is something missing in gang rituals and membership.

These are some of the questions young people are asked to consider in this stage. The main aim here is for the young person to integrate a sense of how they’re shaped by the insights, lessons and challenges of the programme. The focus here is on:

• From self-centeredness to interdependence, sharing and caring;

• Getting involved;

• Understanding that they have something to give;

• Participating and contributing rather than taking or criticising;

• Questioning rather than just doing;

• Developing a different vision for their lives;

• Setting goals and being goal-oriented;

• Taking responsibility for themselves;

• Stepping into leadership.

The Usiko and Chrysalis programmes require young people to undertake scary things like hiking in a wild place, sleeping out alone without a tent and joining ‘Circles of Trust’ where they share their lives, their fears and their hopes. These programmes are powerful and most young people report they are the most important thing they’ve ever done in their lives. This doesn’t mean they wont rejoin gangs, because they go back to the same areas and the same friends. But they return with an understanding of new possibilities and directions that offer them a choice beyond gang life. Many take it.