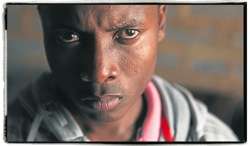

Profile: Tshekiso Molohlanyi

Content partner: Activate! Leadership for Public Innovation

This article was originally published in the Sunday Times, 3 June 2012. It has been reproduced with permission.

When people ask why there is so much violent crime in this country, I want to tell them that I know why. Not the big answer on behalf of all violent criminals in South Africa, but a small answer on behalf of me.

There are things I have done – bad things – which I wish I could undo, but I can’t bring myself to tell you about them. I could give you a fancy reason that I don’t want to incriminate myself because justice is one-sided, but the truth is I’m scared of going back to prison.

I came out of jail consumed by anger but determined to leave the gangster life. As a result I was forced to leave Khuma township near Stilfontein in the North West province and go live with my grandfather in Ventersdorp. Every morning I was sent out to tend his sheep and cattle. He was strict to the point of never talking to me and I spent most days on the hills crying in frustration with only animals to listen. Eventually I cursed myself enough not to care what happened to me and went home to face whatever. Nobody was there to help me bury my past, but me on my own.

During my time in prison, I saw someone being strangled to death and then dismembered into three pieces. No one was charged for that. I feared to talk because I was scared that they would do the same thing to me. I was trapped in a living hell beyond anything I’d experienced outside. I was bullied and spent days without food. My gangster friends deserted me. But actually I went into prison already filled with rage. Prison did nothing to help me, but my fury had preceded it.

It was a fury borne out of bitterness and a desire for revenge. Sometimes I could contain it by smoking dagga mixed with nyaope (one very dangerous drug!) and rat poison. It killed our anxiety and boosted our confidence. It made us fearless and willing to act without hesitation. I craved money and popularity and used drugs to hide my shame and loneliness and battle the demons within me. But that never solved the problem; instead it made matters worse. One day I was alone when I was attacked by rival gangsters. I was stabbed with a knife just above my left eye, dragged behind a moving car and left for dead. Later, I found opportunity to drive my anger through those who had belittled me, but instead of satisfying me that made me even madder.

Yet at home I was small like an ant, obedient like a sheep. Neither my father nor my mother had ever shown me love and I feared them, not without reason. I don’t blame them though; the choices I made were mine. While I was with them, I just bottled up my anger until I could find a place to smash that bottle and hurt somebody with the shards.

The people I hurt often lived on the other side of the mine dump that hides Khuma township from Stilfontein. It’s the side with the lush green golf course and the nice houses. The people who lived there took no notice of us and I felt very small when I went there. It was there that I decided I would definitely be a ‘somebody’ in life, and thought that becoming a gangster would give me the self-esteem I wanted so badly. I was ten years old when I joined that gang.

I’m now part of another gang called Activate! It brings together young leaders from across South Africa, building their sense of identity, belonging and common purpose. That purpose is to make our country a better place. I had completed school after being released from prison, but had no money to study to become the political journalist that I wanted to be. I applied for bursaries and loans, but nobody seemed to want to give money to an ex-convict. So I decided to join loveLife’s debating programme and eventually became a groundBREAKER, one of loveLife’s young leaders. I loved the cut and thrust of debate. A year later, I was thrilled to be given a learnership to study child and youth care work, but it became a dead-end. For some reason, there was no graduation and I am still waiting for my certificate. The whole thing was yet another failure in my life, a fantasy without a happy ending. Still, I kept applying and was appointed as a sports facilitator as part of the Expanded Public Works Programme until March this year. I am now once again unemployed. In fact, to write this article, I had to ask for money to use a computer at an internet café. So mine is not the typical rags-to-riches story you read in newspapers. It doesn’t have a fairy-tale ending, at least not yet.

But I can tell you that I’m never going back to prison and that I’ll always keep hustling for real opportunity. My friends and I would like to start a non-government organisation that can help young people navigate their lives, mediating access to opportunities for education and work. Every community should have such an information hub. I think I can lift my curse by helping other young people who lose hope, bit-by-bit, that their lives will get better.

There are so many other young people out there just like me. Our smouldering anger has few outlets. Lately, several politicians have taken to calling us a ‘ticking time bomb’. They mean well, but they need to understand that the implied threat gives us a perverse sense of power in the same way that gangs hold sway through menace. Please stop defining us in terms of deficit and destructive risk. It feeds our pessimism. It traps us in the prisons of our minds.

I am now free, but to be honest, it’s like I’m out on parole. The circumstances of my life keep threatening to shackle my hopes and handcuff my dreams. I try to stay true to my motto, ‘Asiphelimoya’, meaning we don’t lose hope. I have changed a lot, but I’m also the same person who felt like a nobody in front of white people, whose parents didn’t love me, who did bad things and went to prison, who came out with nobody to talk to and no place to go.

Actually, I’m still motivated by the same basic instincts that caused me to join the gang. I want to belong, to know who I am and to feel that I have a purpose. It was that desire that caused me to join loveLife in the same way as I had joined the B.D.C. gang a decade before. My material condition has not changed much, but I now have some power to respond differently to life’s circumstances.

I’m not suggesting that ‘messing with our minds’ is a substitute for jobs and further education. No, we need jobs. We need places to study and the money to do so. But if you’re invisible to people, you get resentful and helplessness gives rise to anger. You feel like a victim and angry victims want to take back what they think belongs to them. Victimhood feeds a sense of entitlement that devalues education and hard work. Creation of opportunity and a positive psyche must go together.

Many young people in South Africa are still looking for a new identity. They don’t want to be defined as heirs of apartheid, but as shapers of the future. Defining that new identity starts with us, but if older people want to help, they should change the way they talk about us. For example, half of our population is under 25 years of age. Other countries have used a similar phase of their changing age-structure to improve their productivity. We should be asking how we can capitalise on the youth dividend, rather than how we can deal with the ‘problem of youth unemployment’.

We need to build ‘small connections’ for young people in every little town and rural area as much as we develop the grand schemes for jobs and education. If I had had someone to talk to when I was ten or when I left prison, I think I would have been able to channel my rage better. My link to other young people in loveLife made me realise that I was not alone and gave me a few handholds to further opportunities. Even writing this article makes me feel that I am somebody.

Finally, we need role models in our communities who constitute a different sort of gang leader, whom other young people respect and trust. But leadership won’t just happen by itself, or even through training programmes. Those individuals who do benefit will crave to escape from the circumstances that keep pulling them down. We need to learn from the West Sides and the B.D.C’s and the 27’s that leadership development requires systematic organisation and structured networks, so that even the leaders feel that they are part of something bigger than themselves.

***

Activate! Leadership for Public Innovation is a national network of young people committed to social transformation. United across race and class, they will develop the perspectives and skills of innovation needed to tackle some of South Africa’s most challenging social issues.

To find out more, contact Activate! on: info@activateleadership.co.za