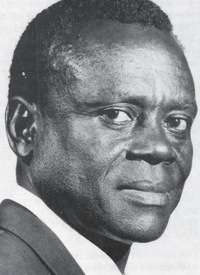

King Edward Masinga, also known as Mangethe, was the first black radio announcer in South Africa.

He was born in 1904 at Mzumbe. His father had run away from home to become a missionary, and had settled down to live at Mzumbe to teach and preach. He was also a builder. K.E. was born there.

When he was six, K.E. started looking after his father’s cattle and goats. He would start his work as a herdboy at 5 o’clock in the morning.

At 8 o’clock he had his breakfast of mealiemeal porridge, and then he went to school until three in the afternoon.

When K.E. was eleven years old, his father died, and the family moved to Inanda. There he went to school at the Ohlange Institute. This school was started by the Reverend John Dube, and the pupils there were called the zebras. This is because Dube means zebra in Zulu. His mother worked as a washerwoman to pay for his schooling.

K.E. said, “To pay for my education, my mother, who was then sixty, took in washing. She walked eight miles to the station every Tuesday, and then took the train another fifteen miles to Durban.

Here she collected a big bundle of dirty clothes, and she returned the same day. Sometimes my sister and I helped her with the bundle from the station.” The clothes then had to be washed, ironed and returned on Thursdays. That meant another sixteen miles to walk and thirty miles on the train.

K.E.’s mother did this every week for nine years.

At the same time, she helped with the hoeing and planting. She died when she was eighty-three.

After leaving the Ohlange Institute, K.E. went to Adams College. He studied there for his matric and a teaching certificate. He worked as a teacher until 1941. He was then thirty-seven years old and dying to try something different.

Two days before Christmas, in 1941, he was walking along Aliwal Street in Durban. He passed a building that had guards outside, and he asked them the name of the building. They told him it was a radio station, but that no blacks worked there, only whites.

K.E. went inside, and straight away he went to speak to the director. That same night, K.E. read the 7 o’clock news in Zulu for the first time. He read it every night after that.

The SABC owned only one Zulu record when he started working there. Soon K.E. started making recordings of the songs he sang when he was a herdboy. “I was always the igosa, the song and dance leader,” he explained, “so I remembered the words and tunes well.” He formed a choir, trained them and conducted them during the recordings. He made records of hymns, Zulu songs, traditional chiefs’ songs and children’s songs. He even recorded the sound effects at the football games. He translated the English news into Zulu. He wrote plays based on the grannies’ stories. He translated nine of Shakepeare’s plays into Zulu. ‘Romeo and Juliet’, a famous love story, was the most popular play.

In 1957, the American Government invited K.E. to come to America for two months to study entertainment and to talk about Zulu music. When he was in America, he said he was very worried that American music would take over in South Africa and make it difficult to keep Zulu music alive. It is interesting to see today that Zulu music is listened to in many other parts of the world, and the group Ladysmith Black Mambazo is very popular overseas.

When he was in America, a woman thought he was Louis ‘Satchmo’ Armstrong. He had to show her his passport to prove that he wasn’t the wellknown trumpeter.

When he was about sixty-seven years old, he started having problems with his eyes, and he became nearly blind. He had many operations, but they did not help. He struggled to see, but he wouldn’t use a white stick. “It is like walking in the dark,” he said.

K.E. married eight times, and had five daughters. All his daughters stayed with him. He was strict with them when they were young. But he was also very jolly, and used to like making jokes and reciting poems to his daughters.

He was invited to many, many parties and weddings and other functions, and people often asked him to give speeches. He never prepared a speech, but just spoke straight away. K.E. liked to sing while somebody played the guitar. He also liked to dress very well. At his home in Lamontville, he had a beautiful flower garden, because gardening was one of his hobbies.

K.E. retired when he was about sixty-five, but was re-employed again by the SABC, and retired finally when he was about sixty-eight.

He died in 1990.

****

Part of an article which appeared in the Sunday Tribune, November 17, 1957

Ex-herdboy guest of U.S.

KING EDWARD MASINGA, so named by his loyal, missionary father, senior Zulu announcer of the SABC in Durban, leaves by plane for America on Monday to study entertainment and broadcasting at the invitation of the United States Government.

Thirty-five years ago, Masinga was a herdboy at Umzumbi. His mother, at her husband’s dying request, educated him by taking in washing.

****

This is part of an article which appeared in the Natal Mercury, January 22, 1958

S.A. Zulu Announcer Returns

“Natal Mercury” Reporter

Mr. King Edward Masinga, South Africa’s Zulu announcer who once composed tribal songs while herding cattle on the veld, has just returned from a two-month trip across the United States.

He gave lectures in some of the leading universities on Bantu cultures. “Everywhere I was asked about the harmony and rhythm in Zulu music and the explanation I always gave was that it was perhaps the product of people who were socially uninhibited and who did not think it was beneath their dignity to sing and strum a guitar in the street,” he said.

His tour had its humorous moments – such as in Dallas, Texas, when a woman was convinced that he was the gravel-voiced trumpeter Louis “Satchmo” Armstrong, and who was surprised when she discovered that he was a real live Zulu. But he had to produce his passport to prove it to her.