I go home to change for the contest. I don’t care if it’s July and winter, I’m so wearing my pale pink shorts and the top that makes me think of the mulberries from the tree in our yard.

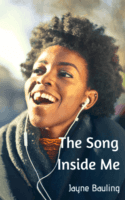

Ma gives my headband and short fro a disapproving look when I come out of my room. I swear, she and Pops would like me to wear Minnie Mouse bundles for the rest of my life.

“I wish you’d rather enter one of those gospel contests,” she says, as I try to settle my stomach by eating something.

“I wish lots of things,” I say, discovering that eating is only making me feel sick, I’m so nervous.

One of the things I wish is that I could have gone to university this year, but no, Sbu is the little lord in our family. And so when he decided he wanted to do a second degree straight after his first one, it was, ‘Sorry, Khaliso’.

I get to work on the flower counter at this big chain-warehouse store in Mbombela, training on the job, learning to make up arrangements and bouquets, sneezing my brains out if there are lilies involved.

If I do well at The Pit, it could be a first step to better things: paid singing gigs, maybe even varsity or college someday. I could end up at the TUT Mbombela campus where Mongezi is studying.

I can’t see him anywhere when I arrive at The Pit. I’m on the edge of panic, because he’s supposed to help with my music. Then my girls find me, and I relax a bit as we push our way through the crowd to get close to the stage. The music is pumping, and Die-Mond is whipping everyone up, ready for the contest.

His name is for the big diamonds he wears in both ears, but a lot of people pronounce it the Afrikaans way. That fits too; his mouth is never still, spitting words like hailstones.

“Die-Mond and the audience are the ones you gotta impress, K-girl, not Mongezi,” Chuma says when I share what Mongezi said about my song.

“Die-Mond and that cute-ass assistant of his,” Wandisa adds.

“You can’t let Mongezi undermine your confidence,” Francine joins in.

“But what if he’s right and my song really does suck?”

My confidence is leaking out of me, the way it always does just before I have to do anything big or important.

“What if the crowd at Giraffe’s Neck are right?” Chuma yells over the music. “The whole lot of them, all those different times you’ve got out there and hit them with your Lyin’ Eyes lyrics?”

“Khaliso Laurel Zitha?”

It’s Die-Mond’s assistant, consulting a list on his phone. He is sort of cute, in an otherwise kind of way. About 19 or 20, medium-length dreads tied up in this little spray on top of his head, Harry Potter glasses, and a very smooth skin.

“Yes?”

He smiles at me. “You’re up tenth and last tonight. You’re using recorded music? Have it organised and be ready to hit the stage when Die-Mond introduces you.”

“Last?” I pull a face. “So I get compared to everyone who’s gone before me?”

“Sometimes that pays off,” he says. “Heard you at Giraffe’s Neck. I believe you’ll kill it tonight, Khaliso.”

***

Tell us: Some people believe it’s a good thing to be nervous before a big competition. Are they right, and if so, why?