And because Dhyan would wait for the moon, his mates in the Army called him Chand, and the name stuck. Dhyan Chandhe was, polishing his skills in the moonlight.

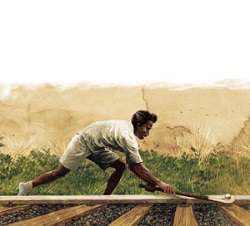

All that hard work paid off for Dhyan. People said he often practised on railway lines, not letting the ball fall off the rail as he ran. That’s probably why Dhyan made a name for himself for his superb ball-control in real games; after all, he had learned it the hard way, on the tracks.

Time and time again during a game, he would run the whole length of the field, opponents sprawling in his wake, ball stuck like glue to his hockey stick until he sent it smoothly past a helpless goalkeeper into the net. The great runner Milkha Singh once asked Dhyan how he had become so good at his game. Dhyan said he used to hang an empty tyre from the goal, and then hit hundreds of shots every day through the tyre. Dhyan scored heavily, and in the years ahead, he would win plenty of games and medals for India.

But what really became his trademark was this incredible skill with his hockey stick, this ability to control the ball as if there was nobody else on the field. As if he was alone again, practising under the full moon.

But his stick skills alone would not have made Dhyan a champion. In the team game that hockey is, Dhyan was also the perfect team man. As he ran up the field, in his mind it was like a chessboard. You know how in your classroom, you can tell just where each of your friends sit? You can point them out, often even without looking: “Kavya’s there. Romil’s over there.” That’s what hockey was like for Dhyan. Without looking, he knew exactly where his teammates were, and to which of them he could pass the ball.

And those pinpoint passes only made him seem like even more of a magician. Long after he retired, he once explained his beautiful game: “The secret is both my hands, and also my mind and fitness routine.”