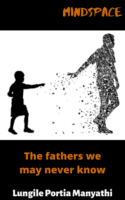

Once, a few friends and I had a heated debate about fatherhood. Whether it was worse to have an absent father, an absent-minded father, or an inconsistent father. Fuelled by experience, we each flung points we felt justified our position on the matter. They spoke of the pain of having to question the whereabouts of a man, a person they felt should have cared enough to make themselves known in their lives. Others, emphasised the pain of knowing the man who was supposed to play an active role in their lives but avoided doing so. Finally, others could testify to the pain of living in a home carried by their mother, in which their father was a shadow that evaded the slightest connection with the children they lived with. When asked what a good father is, none of us could give an answer because even the fairy-tale ideas had long dwindled from our minds. Hence, is the reality for most.

In order to understand the figures we expect to stand beside our mothers and play some kind of role, we could have asked ourselves a few things. Perhaps, we should have questioned what a man is or is supposed to be. We could have gone a little deeper and asked what a boy is or how he should be raised. Finally, we could have searched ourselves for the image of a family that we all have buried in the back of our minds, making us critical of people whose journey we know nothing of.

Culturally, boys are often celebrated at birth and thought of as the future leaders of families, warriors even. They are placed under immense pressure to be strong, dominant and resilient. Often, they are discouraged from showing emotion because that is viewed as a weakness. Most can recall hearing the phrase “Boys do not cry” at some point in their lives. Boys have been expected to imitate the unresponsive character of their forefathers, acting as though nothing in life could affect them. In other cases, boys have had to fill in gaps left by previously absent male figures at a tender age. Either way, the need to show strength has left little room for them to show weakness, seek protection, find comfort or speak of the hardships they endure. It is important to remember that through the years, the resilience of the African male figure has been tested against wars, civilisation, colonisation, and modernisation. Changes that have come at the cost of violence against them, displacement from families, exploitation and confusion to the roles they have to play.

I recently stumbled across a quote that said, “Silence is the symptom of trauma” (author unknown). It brought into context the reality of struggle for the male child. With everything they endure, are they truly given a chance to speak out about their pain, given enough support by family or a society that expects so much from them. With enough pressure, wouldn’t we expect boys to crack and retaliate in different ways against the hardships of growth? If some men can act out abusively, it should not surprise us that others have moulded themselves into impenetrable brick walls. Perhaps, it is those who fear failure that avoid and run away from responsibility. The proper question is, who have boys had to look up to through the years? The reality being that most families are carrying elders who cannot bring themselves to heal, burdening boys with generations of pain or forcing them to fill in for men who never returned.

We could have questioned why the society views the male as nothing more than a provider. Why those who cannot live up to that role, are overlooked or abandoned as weak. Men rarely speak of the hardships cast onto them as boys or the struggles they carry until they become our fathers. They are hardly questioned about navigating through fatherhood (when they are taught to feel nothing) or if they ever find healing from the burdens they carry? We could have asked ourselves whether the boys growing up with us have any concrete idea of what they have to grow into. Also, we could have questioned why (we) girls are being groomed to handle households without them. We should have discussed the uprising of women as a change that does not have to come at the cost of sidelining men. Instead of questioning these cycles of trauma, my friends and I sat debating about the broken fragments of fatherhood we have come to know, from the men we may never know.

This is not to excuse the behaviour of our fathers but rather to question how much we really know about the men we do or do not have at home.

Read about one writer’s conflicting journey to talking to men about issues of feminism here

Tell us: What are your views on fatherhood in African culture?